Beethoven 250: analysis of the composer's letters proves that creativity does spring forth from misery

The notion that artistic creativity and emotional state are somehow related goes back to the time of Aristotle. However, it is extremely difficult to quantify the degree of misery (or happiness) of an artist, and even more so if an artist is deceased. In my research I have found a way to do so by extracting the emotional content from written correspondence.

My research uncovered patterns of emotional wellbeing throughout the lifetimes of creative individuals. During a series of research projects on how geographic clustering of composers influenced their creativity, I found large productivity gains by composers working in locations such as Vienna, Paris and London in the late 18th century to early 20th century. At the same time, it became apparent that in these cities composers have been surprisingly often unhappy or unwell, prompting the question: How do emotional factors influence creativity?

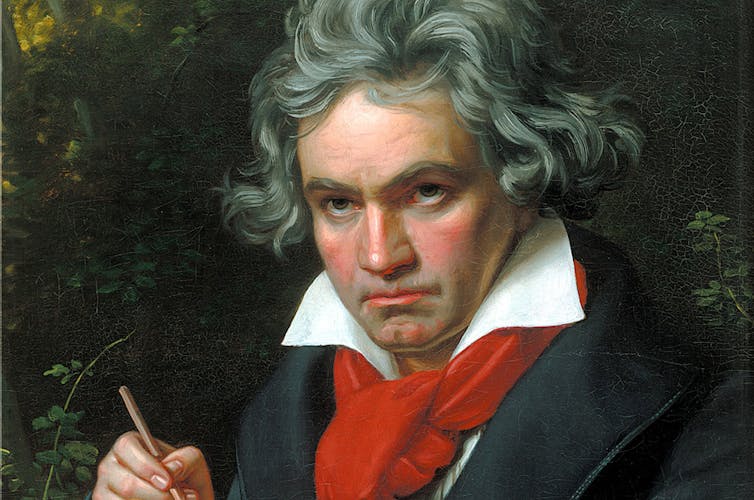

To answer this question I turned to the letters of one of the world’s most famous composers, Ludwig van Beethoven, who wrote over 500 letters throughout his life. Using linguistic analysis software, I was able to reveal how the emotional content of Beethoven’s letters carries the clues to his genius and productivity. I spent months pouring over the letter and creating code, carefully dating each letter. I also spent time distinguishing between different types of correspondent, as he would write differently to family members than to peers or associates.

Beethoven’s wellbeing over his lifetime

The graphs below shows Beethoven’s positive emotions (left panel) and negative emotions (right panel) throughout his lifetime. The rise and fall of Beethoven’s positive and negative emotions mirror the events that took place during his life. For example, an increase in negative feelings during Beethoven’s late teenage years corresponds with the deteriorating financial situation of his family. As a result, Beethoven had to help support his family by taking over some of his father’s teaching duties, to which he had “an extraordinary aversion”.

But Beethoven’s fortunes soon improved. He moved to Vienna in 1792 where he experienced high demand for his work, which bestowed upon him increasingly prestigious commissions. The composer’s positive emotions peaked in this period, and his negative moods were in a steady decline.

Around the turn of 1800, the composer’s life changed forever as he discovered that he was becoming deaf. Correspondingly, we observe a temporary increase in negative emotions as well as a draining of positive emotions, which stay very low but stable over the next 15 years of his life.

In 1809, Beethoven experienced a temporary lift in spirits as his financial stability became secured thanks to a generous grant from the court in Vienna. But the good mood did not last long.

In 1815, Beethoven’s brother died after a long illness. As a result, the composer became the guardian of his nine-year-old nephew, Karl, with whom he went on to have a violent relationship. This left Beethoven a broken man. His positive emotions reached the lowest point of his life, while negative emotions kept on gradually increasing until his death in 1827.

The sad genius?

Looking at the span of Beethoven’s life, the emotional development of the composer is particularly marked by many dark and sad moments. This is not uncommon for famous artists, but the intensity of hardship is particularly striking in Beethoven’s biography.

While his life may have been pock-marked with misery, Beethoven appears to have successfully channelled his negative emotions into his musical output. What I found is that creativity, measured by the number of important compositions, was significantly increased by his negative moods.

For instance, a 9.3% increase in negative feelings provoked by an unexpected event, like a death in the family, resulted in a corresponding increase in creativity and the creation of an additional 6.3% of significant works in the following year.

Read more: Beethoven 250: how the composer's music embodies the Enlightenment philosophy of freedom

Finally, you could ask whether there is any particular type of negative emotion that drives the results. For this reason, I have split the negative emotions index into anxiety, anger and sadness, and found that sadness is particularly conducive to creativity. Since depression is strongly related to sadness, this result comes very close to previous claims made by psychologists that depression may lead to increased creativity.

This constitutes an important insight into how negative emotions can provide fertile material upon which the creative person could draw – an association that has fascinated many since antiquity. But more importantly, on the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth, these results show that all the hardship encountered by the composer has determined his prolific output and bestowed upon him immortal, unforgettable fame. So, as he wrote in his letters: “Farewell, and do not forget your Beethoven.”

Karol J Borowiecki, Professor of the Economic History of the Arts, University of Southern Denmark

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.