Simon Barere’s ‘pearls of sheer light’

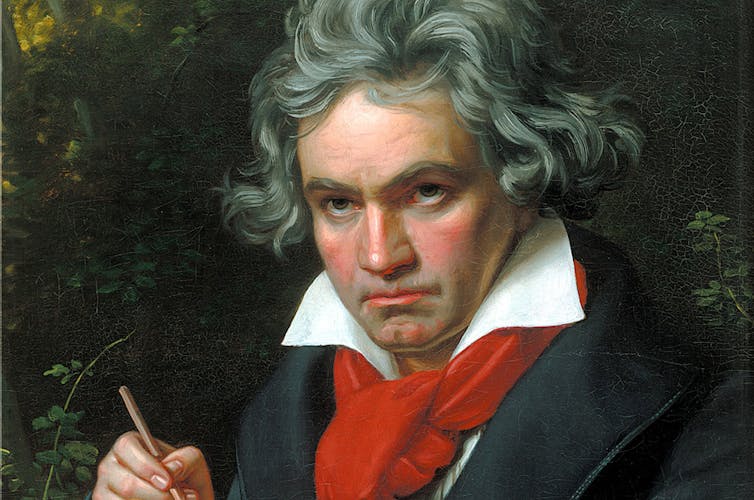

When the thunderous introduction to Grieg’s piano concerto erupted in Carnegie Hall on a spring evening in 1951, the audience was poised for a great musical experience. Pianist Simon Barere (in the picture) was making his first appearance with the Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy conducting.

But at about 2 minutes and 30 seconds into the concerto, as the cellos announce the second theme, keen listeners noticed tempo discrepancies and a wrong note or two.

But at about 2 minutes and 30 seconds into the concerto, as the cellos announce the second theme, keen listeners noticed tempo discrepancies and a wrong note or two.

A member of the audience recalled some years later, “My wife touched my arm in surprise, and I looked at her in astonishment.” Barere had struck a wrong note. Worse, his tempo then began to drag noticeably, and within a few bars he stopped playing altogether and leaned forward.

Barere’s son Boris, now 93 and living in New York, tells me he can still recall the sound of his father’s head crashing onto the keyboard before he rolled to the left and slid off the bench to the floor. The back sections of the orchestra, unaware of the drama, continued playing for several more bars before going silent.

A doctor rushed from the crowd and helped carry Barere backstage where he was given emergency resuscitation. Within a half hour, however, he was pronounced dead of a stroke. The audience, many weeping openly, stood stock still as they took in the tragedy. The world of the piano had just been robbed of one of its greatest Romantic masters. Out of respect for Barere, the rest of the Carnegie program was canceled.

Perhaps given the choice, Barere would have wanted to go out this way. His life, as well as his death, was the piano. He was 54 when he died.

The front-page obituary in The New York Times the next day praised him for his “prodigious technique” and his devotion to music. “Others sought the limelight aggressively,” the Times wrote. “Mr. Barere was concerned with only one thing, the humble service of music.”

In the 1950s world of classical music, Barere was mentioned in the same breath as other superpianists of the era – Georgy Cziffra, Ignatz Friedman, Vladimir Horowitz and Josef Lhevinne. But his most ardent admirers say he was actually in a class by himself. Barere had given frequent solo recitals, sometimes twice a year, at Carnegie Hall to packed houses, with such musical giants as Sergei Rachmaninoff, Leopold Godowsky and Vladimir Horowitz often in the attendance.

Despite his New York success, Barere’s reputation had attracted mainly piano aficianados. His prior European career had been dogged by bad luck and political turmoil, and he was never promoted by managers nor the record companies. And yet at the moment of his death, international success seemed at hand. He had just returned from a wildly successful tour of the United States, South America, Australia and New Zealand.

Admirers were drawn to Barere by two related qualities: his poetic interpretations of the Romantic repertoire and his ability to play at blinding velocity. In combination, these two elements, as in the Liszt E flat piano concerto, for example, still leave many music-lovers awestruck.

One critic, commenting on CD remasterings of his old 78 rpms, wrote that such a cliché as “legendary” actually applies to him. “… far from being an exaggeration, it almost understates his mercurial brilliance”, the reviewer wrote. Gramophone heard the CDs and praised his “freedom and daring”.

Mordecai Shehori, a pianist who has studied his recordings and produced CD compilations under the Cembal d’amour label, compares his rapid pianissimo passages to “a string of pearls made of sheer light”. This quality is especially apparent in his version of the Liszt La Leggierezza.

New generations of piano fans today are just beginning to rediscover Barere as recordings of his 1940s Carnegie Hall recitals and earlier discs circulate on CD. His showpieces such as Islamey and the Schuman Toccata now are uploaded on YouTube and iTunes, attracting thousands of hits.

To better understand this neglected giant, I tracked down several aging witnesses and obtained a dozen CDs of his playing and interviews, including those featuring his son. I found a remarkably uniform – if not quite unequivocal -- assessment.

Jacques Leiser, a retired EMI executive and founder of the Tours Music Festival in France, has carried around memories of a 1947 Barere recital that he happened to attend at the age of 16. He recalls that of all the hundreds of piano recitals he has attended throughout his life, “that one stands out. It just stunned me. Sheer magic, and different from everyone else.”

Leiser says pianists he has worked with in his recording career tend to grope for superlatives, most frequently finding “magic” or “miracle” the appropriate descriptives. “It really boggles the mind why the concert managers and the recording industry of the time passed up this genius,” Leiser says.

Pianist Abbey Simon, one of the great players of his age and still touring at an advanced age, recalled for me what it was like to hear him in person. He emphasized Barere’s “legendary technical facility” and his spontaneity in performance.

Most Barere recordings were live with no retakes or splices. “He was a very free player,” Simon says, “representing a different generation”. Editing techniques now able to cut-and-paste phrases, even individual notes, aim for antiseptic perfection. This is a “disaster”, Shehori says, for players who have more to give than the notes on the printed page, as Barere certainly did.

Even the waspish Horowitz praised Barere’s talents, singling out his recording of Felix Bumenfeld’s Etude for the Left Hand Alone as being “like a miracle”. Legend has it that Horowitz stopped performing it after one hearing. Barere’s secret was not digital dexterity but in the delicate song-like phrasing, which Horowitz apparently felt he could not match.

Barere’s finger speed, although not to everyone’s taste, still in this age of increasingly developed technique among young pianists, was so exceptional that son Boris recalls that he was sometimes thought of as a “neurological accident”. Leiser says simply that Barere’s virtuosity was “on such a high level – so spectacular and so refined – it was an art in itself”.

Barere’s recordings of the Scarlatti sonata in A, Kk113, the Liszt Gnomenreigen, the Balakirev Islamey and the Schumann Toccata, among others, beggar description. The Toccata he races through, to my mind excessively, at 4 minutes 17 seconds (without repeats), resulting in a blur of sound. But he set that breakneck tempo for a reason. He wanted it to fit on one side of the old 78 rpm discs. When asked by Horowitz why he played it so fast, he responded with a twinkle in his eye, “I can play it faster than that.” His Scarlatti comes in at 2 minutes and 51 seconds, compared to four or five minutes in other pianists’ versions.

Barere’s legacy continues to draw criticism today among anonymous YouTube gremlins, one of whom dismissed Barere as a “clown” after hearing the Toccata. But on another level of ambivalence, New York Times critic Harold Schonberg wrote in his biography Horowitz: His Life and Music that Barere had “amazing fingers” but that “his fingers sometimes outran his brain”.

Horowitz, known for his strong opinions on other players, knew Barere personally from their time together at St. Petersburg Conservatory and admitted being “a little bit jealous” of him.

Shehori remembers hearing of a revealing incident at Carnegie Hall that indicates how deep Horowitz’s envy actually was. Violinist Berl Senofsky was seated near Horowitz while Barere performed Liszt's Reminiscences de Don Juan. “As Barere launched into his trademark supersonic chromatic scales in thirds,” Shehori remembers hearing, Horowitz stood up and silently mouthed: ‘I cannot stand this any more’, and left in the middle of the piece.”

I agree with most listeners – pianists and ordinary music-lovers – who praise his sense of phrasing, his tone, color, drive and control. His velocity seems an innate style coming from within rather than being forced or flamboyant.

A natural keyboard genius from the Jewish ghetto of Odessa, the 11th of 13 children, Barere’s personal story is one of missed opportunities and political repression. From an early age, he demonstrated extraordinary memory, technique and depth of musical understanding.

After studying at the Odessa Imperial Music Academy between the ages of 11 and 16, he made his way to the St. Petersburg Conservatory and was lucky enough to be greeted at the door by Alexander Glazunov himself. He played two of his personal favorites, the Liszt Rigoletto Paraphrase and the Chopin C-sharp minor Etude. Glazunov took him directly to the piano department for a repeat performance and all agreed that he must be accepted on the spot. So obvious was his talent that he was spared the entrance exam and the standard Conservatory diet of counterpoint, theory, analysis and musicology.

The Conservatory took him in hand and nourished his talent for seven years, helping him reach beyond technique and into the cosmic potential of great works. Glazunov pulled strings to keep Barere safe from compulsory conscription and to protect him from anti-Jewish restrictions in the Russian capital. Other Jewish musicians, including Horowitz, Nathan Milstein, Jascha Heifitz and Efrem Zimbalist also benefitted from Glazunov’s courageous protection.

Barere studied under two of the leading Russian pedagogues, Anna Yesipova and Isabella Vengerova. His most influential teacher was Blumenfeld, who also taught Horowitz, Maria Grinberg and Heinrich Neuhaus. Following graduation, Barere settled at Kiev Conservatory as a young professor, concertising around post-revolutionary Russia. Boris recalls that on joint tours in the poverty-stricken countryside with David Oistrakh they were often paid in sacks of potatoes.

Travel restrictions imposed by the new Soviet government kept Barere from developing an international career, but finally in 1928 he took a position in Riga, Latvia, as Soviet cultural ambassador to the Baltic states and Scandinavia. Four years later, he was joined by his wife and their 7-year-old son Boris.

Berlin beckoned next, where Barere had a solo debut to great acclaim, only to be nixed by more tyrannical regulations, this time the Nazi exclusion of Jews from German society. Boris recalls that his father’s manager had booked an extensive tour, some 40 appearances, but was forced to cancel all engagements outright. In desperation, Barere helped support the family by providing entertainment in cafes and movie houses, sometimes filling in between jugglers, sword-swallowers and dog acts, Boris recalled in one of our interviews.

Fleeing the Nazis, the family escaped to Sweden where Boris attended school while his father languished in an 18-month period of depression. Eventually while in Sweden, Barere attempted to restart his career, making his first recordings there for Odeon in 1929, featuring Liszt, Chopin and Rachmaninov pieces.

This year is the 80th anniversary of Barere’s 1934 move to London to make his recital debut at Aeolian Hall. Later that year he accepted Sir Thomas Beecham’s invitation to perform the Tchaikovsky piano concerto No. 1. Both appearances set him on a course for international recognition, leading to a series of recordings for HMV, now available on CD under the APR label. Two years later, Baldwin Piano Company invited Barere, now age 40, to move to New York, where he began building a career virtually from scratch.

He toured widely, playing in Australia, New Zealand, South America and throughout the United States. Following his dramatic death, however, public interest waned, and it was two years before a memorial LP album of his best works was issued by Remington.

Barere’s gradual emergence from obscurity today can be credited in large part to Bryan Crimp of Archive Piano Recordings (APR) who had been drawn to Barere for his “phenomenal technical security and wonderful phrasing”. Crimp took on the task of salvaging the entire Barere oeuvre that existed in random locations on acetate and shellac. With the active assistance of son Boris, the recordings were assembled by venue and period, mostly with exact programs as performed, and remastered.

Crimp went to far as to salvage two recordings that would have been lost – his Beethoven Sonata 31 in A flat Opus 110, and Chopin’s Ballade No. 4 in F, Opus 52. Crimp says surface noise was so extreme when he first heard them that they were excluded from the project. But digital technology improved rapidly through the 1990s, enabling sonic programs to ease the noise and enable their first release.

It is only the dedication of a few individuals, and the impact of digital technology, that Barere’s rich legacy of piano genius has been saved from oblivion.

This article appeared originally in the current edition of International Piano.

To follow what's new on Facts & Arts, please click here.

This article is brought to you by the author who owns the copyright to the text.

Should you want to support the author’s creative work you can use the PayPal “Donate” button below.

Your donation is a transaction between you and the author. The proceeds go directly to the author’s PayPal account in full less PayPal’s commission.

Facts & Arts neither receives information about you, nor of your donation, nor does Facts & Arts receive a commission.

Facts & Arts does not pay the author, nor takes paid by the author, for the posting of the author's material on Facts & Arts. Facts & Arts finances its operations by selling advertising space.